Speaker Identification

Phonexia Speaker Identification (SID) uses the power of voice biometry to recognize speakers by their voice… i.e. to decide whether the voice in two recordings belongs to the same person or two different people. Our goal as a regular participant of the NIST Speaker Recognition Evaluations (SRE) series is to contribute to the direction of research efforts and the calibration of technical capabilities of text-independent speaker recognition. The objective is to drive the technology forward and through the competing find the most promising algorithmic approaches for our future production-grade technology.

Basic use cases and application areas

The technology can be used for various speaker recognition tasks. One basic distinction is based on the kind of question we want to answer.

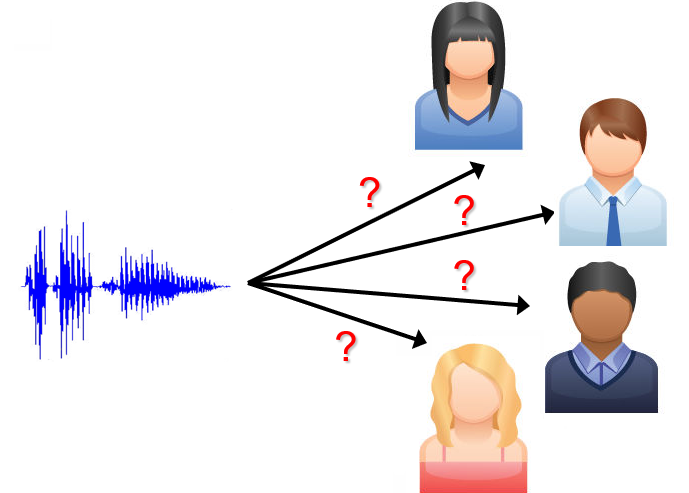

Speaker Identification is the case when we are asking “Whose voice is

this?”, such as in fake emergency calls.

Usually this entails

one-to-many (1:n) or many-to-many (n:n) comparisons.

Speaker Search is the case when we are asking “Where is this voice speaking?”, i.e. when looking for a speaker inside a large archive.

We have to do with Speaker Spotting when we are monitoring a large number of

audio recordings or streams and we are looking for the occurrence of a specific

speaker(s).

Speaker spotting can be deployed for the purpose of Fraud

Alert.

Speaker Verification is the case when we are asking “Is this Peter

Smith’s voice?”, such as when a person calls the bank and says, “Hello, this

is Peter Smith!”.

This approach of one-to-one (1:1) verification is

also employed in Voice-As-a-Password systems, which can add further security

to multi-factor authentication over the telephone.

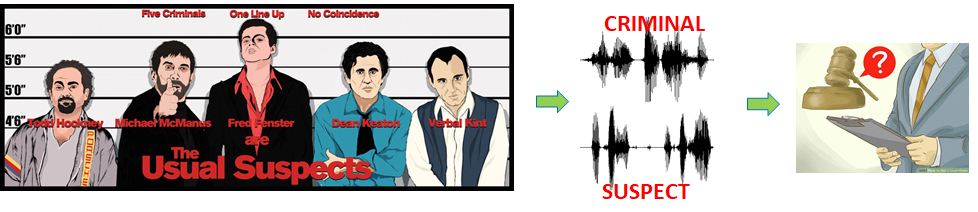

Large-scale automatic speaker identification is also successfully used by law enforcement agencies during investigation for the purposes of database searches and ranking of suspects. In later stages of a case, Forensic Voice Analysis uses smaller amounts of data and 1:1 comparisons to evaluate evidence and to establish probability of the identity of a speaker and use it in court.

How does it work?

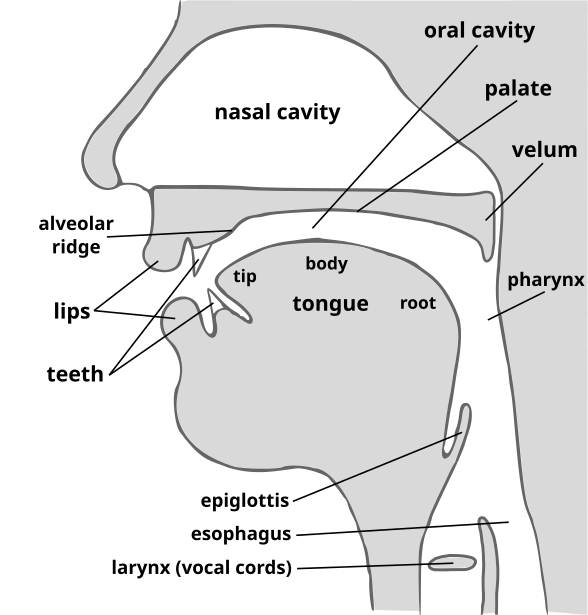

The technology is based on the fact that the speech organs and the speaking habits of every person are more or less unique. As a result, the characteristics (or features) of the speech signal captured in a recording are also more or less unique, thus the technology can be language-, accent-, text-, and channel-independent.

Automatic speaker recognition systems are based on the extraction of the unique features from voices and their comparison. The systems thus usually comprise two distinct steps: Voiceprint Extraction (Speaker enrollment) and Voiceprint comparison.

Voiceprint extraction is the most time-consuming part of the process. Voiceprint comparison, on the other hand, is extremely fast – a millions of voiceprint comparisons can be done in 1 second.

Voiceprint

A voiceprint (also x-vector or i-vector) is a fixed-length matrix which captures the most unique characteristics of a speaker’s voice. Voiceprints are unique to every individual, similar to fingerprints or retinal scans.

Voiceprint file

The internal structure of the voiceprint consists of a header (metadata information) and a data part that contains characteristics of the speaker's voice. The structure and length of a voiceprint is always the same, regardless of the length and the number of the source recordings. A voiceprint created from a single short recording will always be the same size as a voiceprint created from 80 different long recordings. The exact number of digits may vary depending on the technology model selected.

What can be learned from a voiceprint?

- Similarity to another voiceprint

- Speaker’s gender

- Total length of original recordings

- Amount of speech used for voiceprint extraction

What can't be learnt from a voiceprint?

The Phonexia Speaker Identification technology's most important feature is that it prevents the retrieval of the audio source, call content, or original voice sound from a voiceprint. The voiceprint file only contains statistical information about the unique characteristics of the voice, but never information useful for reconstructing the contents of the audio (i.e. who said what) nor for voice synthesis systems (TTS - Text to Speech).

Backward compatibility

Previously, a voiceprint created by a Speaker Identification model could only be used with that specific model. For instance, it was not possible to compare a voiceprint created by the XL3 model with the XL4 model. However, XL5 offers backward compatibility, meaning that it can create voiceprints that can be compared with XL4 voiceprints.

This is possible because XL5 voiceprint extraction emits two subvoiceprints: a new XL5 voiceprint and an XL4 compatible voiceprint (not the same as XL4).

- XL4 voiceprints cannot be converted to XL5, but it is possible to compare XL5 and XL4 voiceprints using the XL5 comparator if XL5 voiceprints have been extracted in compatibility mode.

- XL5 voiceprints extracted in compatibility mode are comparable only with XL4 voiceprints, comparison with older voiceprint generations (L4, XL3, L3,...) is not supported.

- Comparison mode is turned off by default.

Voiceprint encoding

Although the information conveyed by the voiceprint is identical in both microservices and Virtual appliance, the way this information is represented, that is, its encoding, differs.

The format used for Virtual appliance is Base64. This is because the format used for REST API calls and responses is JSON. Since JSON is a text-based format and can only directly handle text or numerical data, voiceprints, which are binary data, must be converted. The most common method for encoding binary data for JSON is Base64 encoding.

In contrast, the gRPC API can directly handle binary data, therefore in the case of microservices, the used encoding is UBJSON (Universal Binary JSON).

Irrespective of the manner in which the voiceprint is encoded, there is no requirement to decode it. A user may store the encoded voiceprint for subsequent comparison. The process of decoding and subsequent encoding would result in the unnecessary consumption of resources.

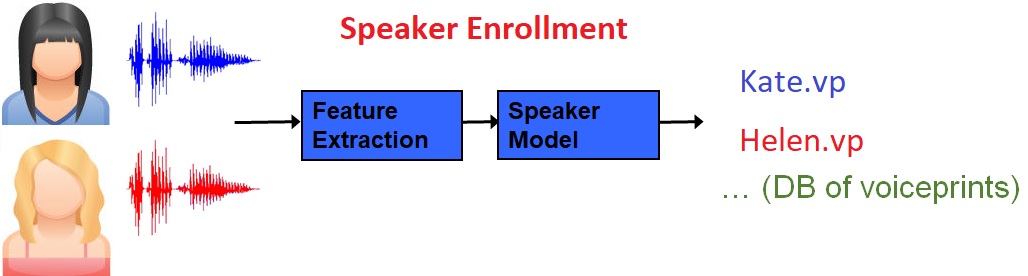

Voiceprint extraction (Speaker enrollment)

Speaker enrollment starts with the extraction of acoustic features from a recording of a known speaker. The process continues with the creation of a speaker model which is then transformed into a small but highly representative numerical representation called a voiceprint. During this process, the SID technology applies state-of-the-art channel compensation techniques.

Voiceprint comparison

Any voiceprint of an unknown speaker can then be compared with existing enrollment voiceprints and the system returns a score for each comparison.

Scoring and conversion to percentage

Score produced by comparing two voiceprints is an estimate of the probability (P), that we get the given evidence (the compared voiceprints) if the speakers in the two voiceprints are the same or if they are two different people. The ratio between these two probabilities is called the Likelihood Ratio (LR), which is often expressed in the form of a logarithm as Log Likelihood Ratio (LLR).

Transformation to confidence (or percentage) is usually done using a sigmoid function:

where:

shiftshifts the score to be 0 at ideal decision point (default is 0)sharpnessspecifies how the dynamic range of score is used (default is 1)

The shift value can be obtained by performing a proper SID evaluation – see

the chapter below for details.

The sharpness value can be chosen

according to the desired steepness of the sigmoid function

- higher sharpness means more steep function – i.e. more sharp transition between lower and higher percentages, and only small differences in the low and high percentages

- lower sharpness means less steep function – i.e. the transition being more linear

The interactive graph below should help you to understand the correlation between score and confidence via the sigmoid function steepness, controlled by the sharpness value.

SID evaluation

Before implementing Speaker Identification, it’s important to evaluate its accuracy using real data from the production environment. To evaluate the SID system, you’ll need enough of labeled data, i.e. recordings with speaker labels.

The principle of SID system evaluation is to compare (voiceprints of) all the individual recordings against each other and check the results of all the comparisons. Since it’s known which comparison is which – which compares the same speaker (called target trial) and which compares different speakers (called non-target trial) – it’s also known which comparison should give a high score and which should give a low score.

In the process of voiceprint comparison, two types of error can occur:

- False Rejection occurs when the system incorrectly rejects a target trial, i.e., the system says that the voices are different even though in fact they belong to the same person

- False Acceptance is when the system incorrectly accepts a non-target trial, i.e. the system says that the voices are the same, even though they belong to different persons.

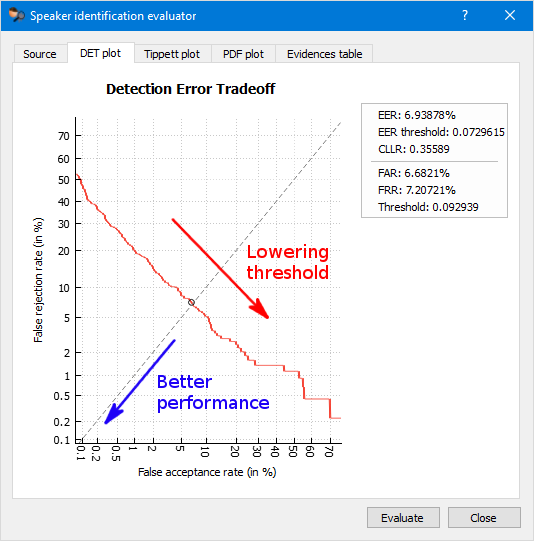

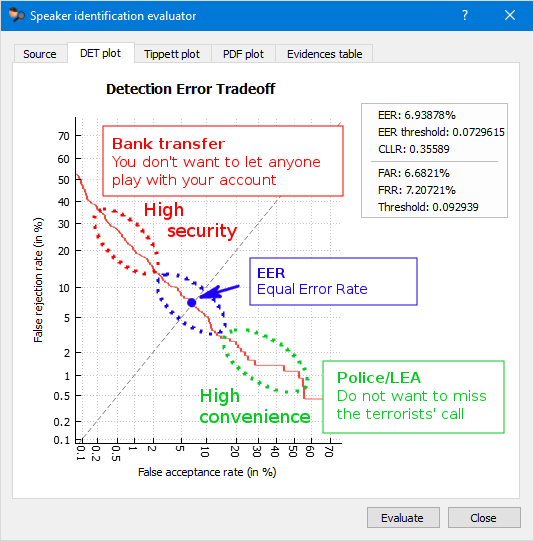

One way to measure the performance of a Speaker Identification system is to calculate the trade-off between these two errors which can be shown in a Detection Error Tradeoff (DET) graph. By decreasing the threshold for acceptance we decrease the probability of a false rejection, but at the same time we increase the probability of a false acceptance.

In an ideal system, we want both errors to be as small as possible. Better

performance is indicated in a DET graph by the red line being closer to the

origin (0 at both the x and y axes).

By properly setting the acceptance

threshold the system can be adjusted for a particular use case.

For

example, in the case of voice-as-a-password for the authentication of bank

transfers when high security is desirable, the threshold should also be

high.

For law enforcement agencies looking for any leads in a case, a

higher false acceptance rate is an acceptable price to pay for not missing a bad

guy’s call.

The operating point of the system when it makes the same number of false acceptances and false rejections is called Equal Error Rate (EER). It is a common measure of the system’s overall performance.